Guest Writer: Father Moo

Analog is the newest hottest thing on the music scene. It’s also old as hell. The only thing older than analog synth technology is tube synth technology, and I don’t own a Metasonix S-1000 or a Wretch Machine, so I’m not gonna lecture you on them. (However, if anyone wants to give me one of those to write a review, I’ll take it!)

I’m not here today to talk about why analog sounds good. It obviously does. Whether it’s a completely pure analog signal chain, or a mostly-analog signal chain with some digital control, it sounds good. No, what I really want to talk about today is that analog synthesis, the preset-free version of analog synthesis, really forces you to be creative due to the limitations of its design – and those limitations can be put to work for you.

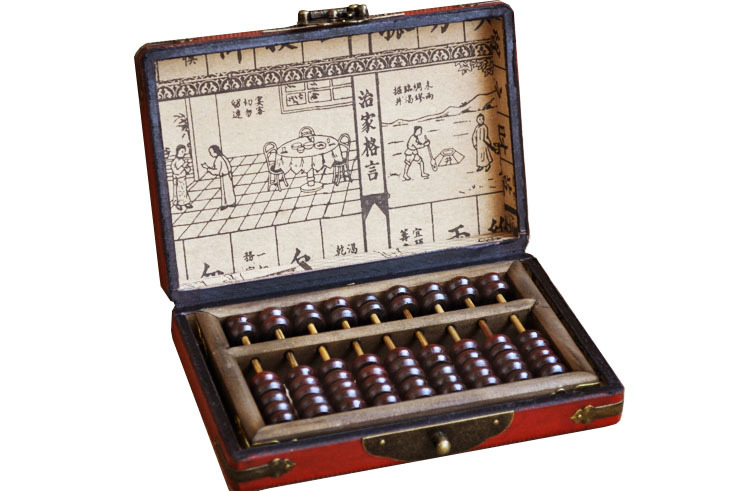

First of all, an analog synth is actually an analog computer. There aren’t many analog computers around us in the modern world – if you have a mechanical watch or you use an abacus, you might have come into contact with an analog computer. Each has a simple output: the mechanical watch tells you what time it is now, but usually just in one place. And an abacus can be used for calculation of sums, but when you’re done adding things up, you reset it to zero. Neither has a save state, neither can back up its data.

<Image: Abacus>

For the most part, analog synths also have a single output, which is determined by the positions the knobs and buttons are in. If you make a cool sound, and you want to be able to use it again, you’d have to note down the positions of the knobs and buttons on a piece of paper, or maybe take a photo with your cell phone (a function that the synth programmers of the 70s had to outsource to their Polaroid cameras).

The analog computer doesn’t really have a save state. It can’t recall presets quickly. This encourages the user to come up with new sounds constantly, and also to record good sounds when they’re created. But this forces the musician to create new sounds, to experiment constantly. And even when a sound is saved on a piece of paper, the live performer can use that as a starting point to tweak in real-time, to twist knobs while soloing. You quickly learn which knobs are suitable to play around with in real time (filter cutoff, LFO speed) and which not to (oscillator pitch).

Presets have their place, and almost all synth users rely on presets to some extent. But I’m here to urge you to keep at least one analog synth in your life to keep yourself questing for new sounds.

One analog synth that I bought, sold, and then bought again is the Korg Monotribe. It’s ideal for demonstrating the arguments of this article, for the following reasons:

-

It’s almost completely ‘what you see is what you get’ – almost completely knob-per-function

-

It contains an analog monosynth, sequencer and drum machine

-

It contains a built-in speaker

-

It allows you to save exactly one sequence (both quantized and unquantized) and one drum program

-

It runs on batteries and is about the size of a hardcover novel.

Notice here that I’ve said nothing about how it sounds. In my opinion, the monosynth is very good, especially the filter sound and the wide range of the LFO. The 3 drum sounds are all useable, but get boring after a while since they cannot be modified in any way. But that’s not the point.

<Image: Monotribe>

No, the point of the Korg Monotribe is that it can’t save sounds as presets. Wherever the knobs are set, that’s what it sounds like. You simply can’t fall back on preset sounds because there aren’t any. In fact, even if you took a picture of it, it’d be hard to see what the knobs are set to.

I never bother to create ‘presets’ for the Monotribe. What I prefer to do is to have it with me when I’m watching TV. I’ll tweak the knobs until I get an interesting sound, and then run the sequencer until I come up with something interesting there too, and I use the drums as a metronome at first until I come up with something suitable. Or maybe I’ll start with the drums and work my way back to the monosynth. I may even set the tempo real slow and use the LFO to modulate the pitch to create an atonal generative patch for a background soundscape. Since it’s small, runs on batteries and has an internal speaker, I don’t need to hook up my whole studio. I just have the Monotribe in front of me as I watch my show and after a while I’ve come up with a cool sequence and drum pattern, the basis of a future track. Then I save the sequence to the single memory slot, and I power down the synth and set it aside. A day or two later, I’ll be planning to record some music, and wait – isn’t there a cool sequence saved in the Monotribe? Indeed there is, the perfect starting point. Especially for Berlin School type tracks, I’ll run it through my Boss RE-20 Space Echo (emulation pedal), and then straight into my hardware recorder. Or, now that I have a Korg Monologue and an Arturia Impact, maybe this will be the start of a multi-groovebox jam session. The sequence I saved while watching TV is the starting point, and I’ll run the hardware recorder and tweak the sequence in realtime, maybe recording over my original pattern using the ribbon keyboard and a guitar pick. Here’s one of my old tracks, made with a Monotribe sequence first and with a few hardware synths overdubbed later. – Alphane Moon Clan

And when I’ve laid that track down, I’ll put the Monotribe aside until I’m watching TV again some evening, and then hey, maybe I should come up with a new sequence. After all, I’ve already recorded the one I made before. I don’t want to keep tweaking that old one, and probably the recording process changed it and it’s preset sound beyond recognition. So I guess it’s time to come up with a new sound and a new sequence and a new drum pattern altogether.

Of course, all synths can be wiped and you can always start again. But if you have a digital synth with 100 presets, you find yourself relying on your favourite sounds more than coming up with new ones from scratch. Or at least I do. Same thing in PC recording – you’ve got dozens of great presets and drum loops, and you tend to fall back on the reliable tones.

The Monotribe doesn’t have anything reliable. It just has the last sound you made, and you’re bored of that sound. So make a new one.

There are other synths without memories. I think everyone who makes music should have at least one for their own creativity. Whether it’s a vintage monosynth like the Yamaha CS-15, or something new and affordable like the Behringer Neutron or the Moog Grandmother, get yourself something that’s a real blank slate, something that forces you to start from scratch every time, and you’ll find new sounds are almost forcing their way out of your synth.

<Image: Yamaha>

Someone on the internet once said that the Monotribe isn’t a synth, it’s a “little boom box receiving alien radio transmissions from the edge of the universe.” Trust me, you don’t want to miss out on those transmissions. They’re playing the hottest, newest sounds I’ve ever heard.

Five Tips for Going Analog:

-

Dip Your Toes In The Water: Even if you generally prefer working in a DAW or with digital gear, you can go analog on a small budget. These days, the cheapest options are the Korg Monotron Duo and Delay, which pair well together and can be used to make an interesting range of weird sounds. They have no presets so you’ll always be experimenting.

-

The Next Level: for a little more money, you can get a Volca analog synth (which will have presets), or a Monologue, which at least has a mode that will initialize the sounds based on the current knob positions. Or how about the Trueno analog synth on a USB stick? It’s a good option for DAW users.

-

Reboot your Brain: even if you have a synth that has preset memories, try initializing a patch and making one yourself, from scratch. Force yourself to develop the basic patches: lead, bass, pad, etc.

-

Audio Input: If your analog synth has an input, run everything weird through it that you can. That includes radio broadcasts, TV, a mic, a crappy kids toy digital synth. Mangle the sound using the filter and LFO, or go farther by adding guitar pedals to the signal chain. Don’t forget to record the output for future sampling!

-

DIY: Build something analog. These days there are tons of cheap DIY kits on the web. Make (or at least assemble) your own module or weird sound generator. No matter what you build, I highly doubt it’ll have presets!

討論區

目前尚無評論